Alexandra Landré gives an introduction to the project and a résumé of our observations and questions from five editions of the TBDWBAJ project:

Observation I

What is most striking about the matrix of all participants is that they all experienced violence in early childhood and that even years later they do not view this as deviant behaviour of people in their environment, but as “normal”. They place the blame for their situation in life — as a drug addict in prison — on themselves and the way they lead their lives.

Questions:

Do we need to view this violence as a commonplace way of behaving in our society? To what extent can one speak of collective acceptance of violence in the private sphere or is it a general ignorance of what actually happens behind closed doors?

How applicable are the circumstances obtained in the private closed sphere to the prevailing socio-political structures of individual countries? This is discussed based on the following keywords:

Power — state authority, power — self-determination

State authority — parental authority

Appreciation — grief, or rather the confirmation by society that one has indeed experienced things that are unequivocally and without any doubt to be grieved over.

Observation II

The results and knowledge attained through the TBDWBAJ project were not achieved with the intention of triggering short-term emotional dismay or compassion that remains without consequences, for this only consolidates existing biases in hierarchies. For this reason, TBDWBAJ refuses to present shocking or sensational images from inside the prisons, or of junkies marked by their suffering. Rather, the project is about the finding and naming of facts, so that the subject of incasts and outcasts can be viewed from various perspectives, circumscribed, and carried over into a more extensive discourse. However, the finding and naming of facts is only possible if everyone involved is prepared to be open with each other, and a relationship of mutual trust has evolved. The purpose of exchanging views is to find a way out of the private sphere of intimate relations and into the public sphere of human intervention, which requires and includes reflecting and taking a stance.

Questions:

To what extent can carrying the discourse forward and extending the radius of action, as well as the knowledge gained from this, influence or change the treatment of a marginalised group and each of its members, and can this initiate critical reflection of accepted or established positions?

Observation III

Action is one of the instruments through which a democratic, pluralistic society continuously realises itself and re-forms. This process is mirrored in the public sphere, for example, in the processes whereby decisions are made about which kind of groups are welcome and accepted, and which are actively marginalised — incasts and outcasts. The exclusion of a particular group in itself puts a question mark on both pluralism and democracy. Further issues are: according to which criteria are such decisions made about which individual is assigned to which group, whether somebody is welcome or not, or is even repelled. Is it possible to intervene in this process?

Questions:

Can one actually still speak of a democratic public sphere if marginalised groups are denied access or excluded, and who makes which decisions on this matter?

Is the de-democratisation of society the consequence of this de-democratisation of the public sphere?

Observation IV

TBDWBAJ operates at the interface of violence and power, action and the public sphere. To shed light on a socially isolated marginalised group and make these “invisible ones” visible via their biographies in an art project, is a sensitive matter in any society because immediately the finger-pointing and recriminations start. A predominant majority is of the opinion that drug addiction is based — like every other instance of non-functioning — on personal incapability and the addicts themselves should shoulder exclusive responsibility for the consequences of their addiction. The use of the repertoire of art in the process of research and the creation of objects to represent the results passes on information to others and brings out past events from the shadows into the light. This can initiate a more differentiated way of treating the subject.

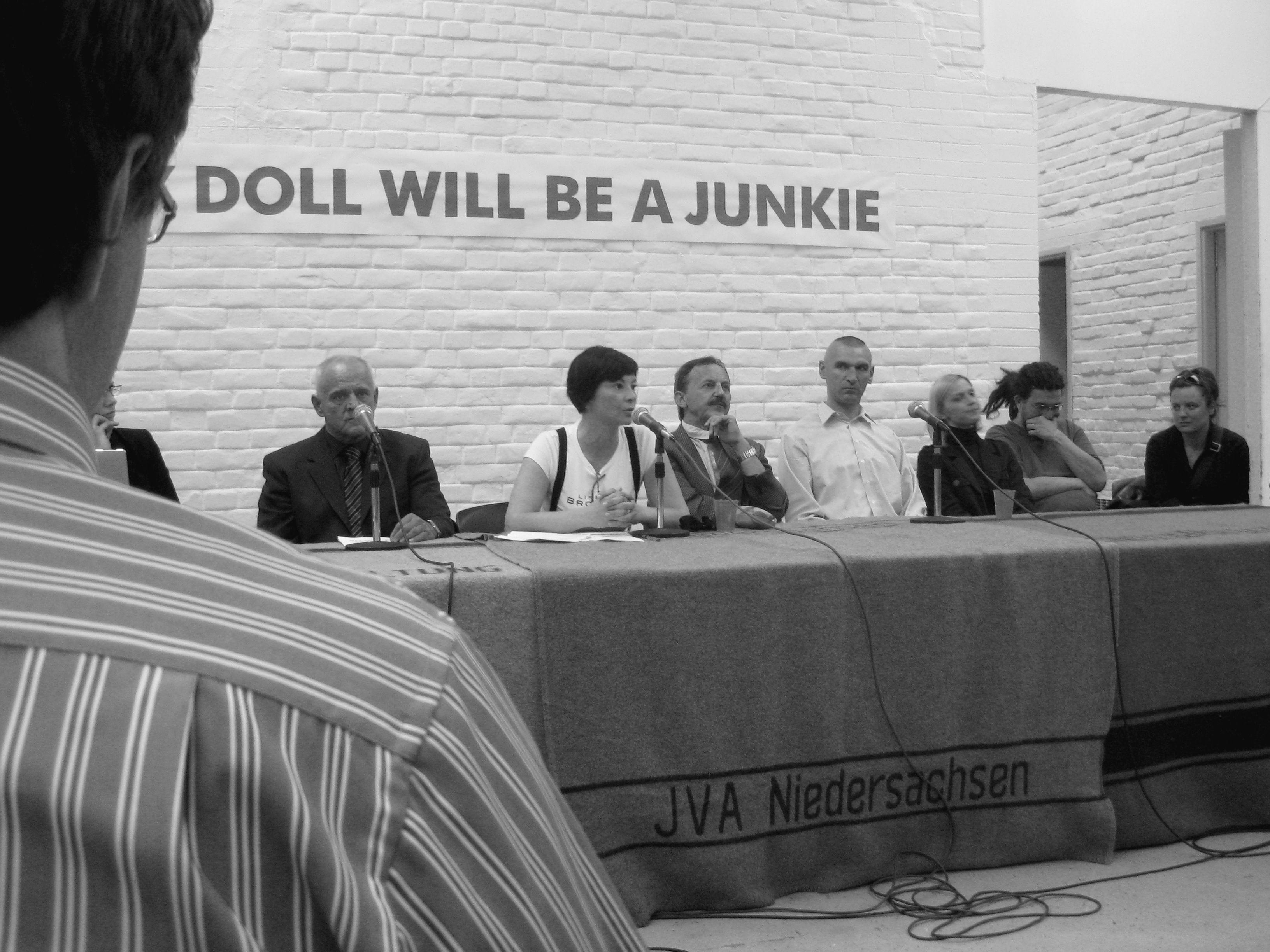

Conversation

Nataša Škaričić thanks the Dutch curator for her observations and questions. Moderation of the following discussion takes place in Croatian. The transcription, which is translated by Iva Prosoli, records the progress of the debate, in which mainly the significance of the TBDWBAJ project for the Croatian judicial system and health care is discussed: Is this kind of art practice a sort of luxury, or is it a good alternative to the current treatment of drug addiction? Can art projects which have emancipatory effects compensate for the weaknesses of institutions? What could be taken over from TBDWBAJ into treatment concepts, and do the results of the project change established views?

Slavko Sakoman is a recognised authority in the field of psychiatric treatment of drug addicts. He, too, emphasises the importance of a gender-specific approach in addiction treatment. Women are disproportionately often the victims of psychological, physical, as well as sexual abuse.

A recent study done in many European countries — including Croatia — on the victims of social intolerance confirms that at the top of the list of various social categories are drug addicts, whereby women are far more affected than men. Especially in the case of pregnant women or mothers, rehabilitation contains far too many negative factors, which make it almost impossible.

In the view of Robert Tore, a practising psychiatrist for drug addicts, TBDWBAJ is not art therapy, but one of the first projects in which contemporary art engages with this subject both socially and politically.

The sociologist Benjamin Perasović supports everything that contributes to the “evolution of awareness”: “TBDWBAJ makes it very clear that we live in a society in which the socialisation patterns of patriarchy and traditionalism are accepted completely blindly and without question.”

Perasović’s first experience with strategies and treatment of drug abuse was around ten years ago in California and the Netherlands with interest groups organised by women: “…and if TBDWBAJ leads some women in or out of prison to organise in a similar way, then I will support it.”

Vesna Babić, head of the government office against drug abuse, praises the fact that the inmates of Požega prison shared their life experiences so optimally: “If something can be brought into the closed prison system from the outside, then the therapeutic efficacy for the participants is really superb and thus legitimises the project.”

Chief of Police Dubravko Klarić defends the existing institutional system in Croatia. The institutions are not incapable of engaging with the problem of drug abuse. In his nearly forty years with the police, he has frequently been confronted with drug addiction and drug-related crime. The government increasingly invests more funds in resocialisation, education, and aid, and since 2009 has launched a new strategy with a focus on prevention and resocialisation.

The lawyer Ljubica Matijević Vrsaljko thinks that TBDWBAJ does indeed demonstrate “the inability of the institutions”. In this context, she has often defended indicted women in both the criminal and also in the general sense. She gives keywords: rape, poverty, drugs. And it is very important to raise questions about the children of these drug-addicted women. What chance does such a child actually have at all? “When women are released from a penal institution, they are confronted with problems such as unemployment, stigmatisation, and poverty. The custody of their children has often been taken from them. What chances do they and their children actually have at all?”

She believes that this project could engender a new sensitivity in the audience: “It is extremely important that society is not indifferent to the problems of these women and their children.”

Nataša Škaričić enquires about the significance of socially committed art in Croatia and notes that here in fact two areas are addressed where Croatian society lacks awareness: art and social problems.

The artist Barbara Blasin disagrees. Socially committed works are by no means a rarity in contemporary art production in Croatia, and they play a significant role in raising public awareness, in spite of the fact that the media seldom perceives them as art projects. She thinks that situating the TBDWBAJ project in different spheres is very effective because the personal stories of the women are brought out of the isolated environment of the prison into the public sphere in such a memorable way.

The artist Kristina Leko confirms that there is considerable interest in community art. Although her own projects are mainly done outside the country, she also creates works in Croatia together with socially precarious groups such as immigrants and workers. Here the concepts of “democratisation of art, and social participation in realising an artwork” are of great significance. In the Croatian situation this has developed well as collective art practice; collaboration with institutions, however, is non-existent. She commends the prison for making TBDWBAJ possible and sees this as a good sign that these social institutions are actually interested in this thematic complex.

In projects staged in public spaces, the artist Iva Kovač especially looks at how a work of art articulates itself: “It is of special importance to find the right model for communicating with the public.”

That TBDWBAJ operates in several different spheres is, in her view, the appropriate method to best articulate prison work and the associated discourse. She queries, however, whether the people who find the Baby Dolls after the Drop Off are clear about what it is actually all about.

In Kristina Leko’s opinion, everybody is responsible for what happens to the Baby Dolls. She and her colleague simply could not abandon the Baby Doll and leave it on the ground: “Our Drop Off spot was in front of a police station. We agreed with the head of police that the Doll will in future be a demonstration object for police work.”

Sanja Sarnavka describes the strategy of the NGO B.a.b.e., and in this context emphasises how important it is to collaborate with institutions because this makes projects such as TBDWBAJ possible. She also mentions successful examples of collaborations with artists like Sanja Iveković and Barbara Blasin.

After the discussion, Vesna Babić hurries off into the city. She was hoping to adopt one of the Baby Dolls. However, all of the Dolls had already vanished.

Transcription: Iva Prosoli

Summary: Ulrike Möntmann/ Nina Glockner

Participants:

TEILNEHMER:INNEN

Alexandra Landré, Moderation

Nataša Škaričić, Moderation

Vesna Babić, Leiterin des Regierungsamtes gegen Drogenmissbrauch

Barbara Blasin, Künstlerin

Dubravko Klarić, Berater des Regierungsamtes gegen Drogenmissbrauch

Iva Kovač, Künstlerin

Kristina Leko, Künstlerin

Željko Mavrović, ehemaliger Box-Schwergewichts-Europameister, heute tätig inHilfsorganisationen für Drogenabhängige

Benjamin Perasović, Soziologe

Slavko Sakoman, Arzt

Sanja Sarnavka, Vorsitzdende der NGO B.a.b.e.

Robert Torre, Psychiater

Ljubica Matijević Vrsaljko, Rechtsanwältin und ehemalige Ombudsfrau für Kinder

Maja Vučić, Psychologin