This meeting of experts addresses the revolving door effect of women with drug use disorders in prison in Austria. The diagrams on offences 1 + 2 were explained, discussed and expanded, in which offences committed are compared with the offences suffered by the project participants from the Schweizer Haus Hadersdorf therapy centre (Vienna, 2022) and the Schwarzau prison (Schwarzau am Steinfeld, 2023). Insights from research projects conducted by the experts in Austrian prisons will be discussed and compared with experiences and findings from the PARRHESIA project implementations in Austria. Aspects of the availability of counselling, support and substitution after release from prison will be discussed.

OPENING

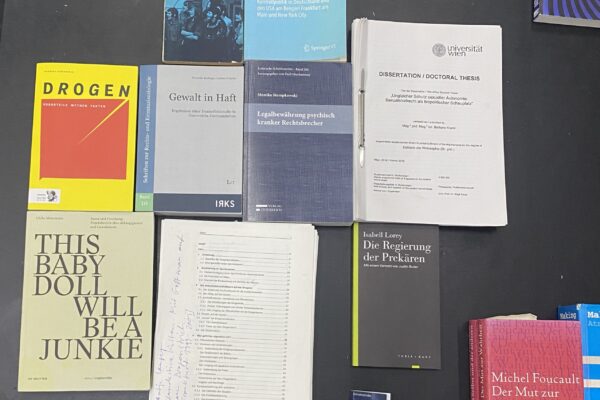

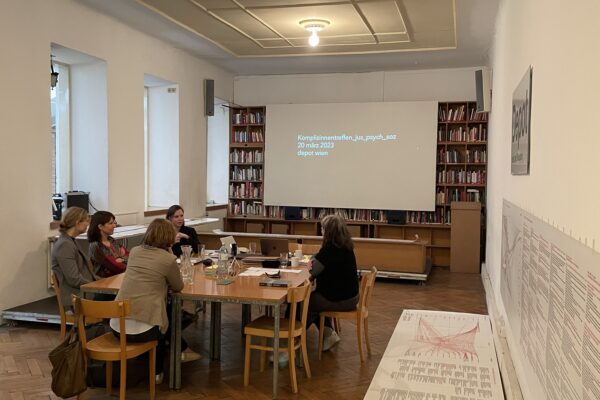

The first ‘Accomplices' Meeting‘ of Ulrike Möntmann's new arts-based research project PARRHESIA – The Risky Activity of Speaking Up and Speaking Out about Drug use took place in March 2023 at Depot Vienna, after two intensive working phases in the Austrian women's prisons Schwarzau and Schweizer Haus Hadersdorf Vienna. The project's internal discussion format, in which expertise from theory and practice from various fields of work and research disciplines are brought together, proved successful in the previous project THIS BABY DOLL WILL BE A JUNKIE (TBDWBAJ, 2004–2019) and is now an integral part of Ulrike Möntmann's artistic-scientific research. Complementing the regular public Expert Meetings, it provides critical reflections from a range of perspectives to accompany the individual project phases. In a three-hour discussion, Ulrike Möntmann, together with her colleagues Stefanie Elias and Stefan Auberg, presents the results to date and discusses them with her ‘Accomplices’ Veronika Hofinger, Barbara Kraml, Johanna Meyer and Monika Stempowski from psychological, legal and social science perspectives.

The following summary does not claim to be complete, but is limited to a fragmentary reproduction of the topics discussed, which are important for the further development of the project.

At the beginning of the conversation, Ulrike Möntmann briefly outlines the status quo: her new project is once again concerned with women with drug addictions in European prisons. While TBDWBAJ focused on Western and Eastern Europe, the individual PARRHESIA projects are to take place on the North-South axis, which, however, has been considerably complicated by the coronavirus pandemic, in addition to the often limited willingness of institutions to cooperate.

The title and thus the central concern goes back to Michel Foucault's examination of ancient Greek society. ‘Parrhesia’ refers to the courage to speak the truth under risky conditions, because the outspoken, critical public speaking of an individual whose social position is below that of those in power can have unforeseeable consequences. And that is precisely what it is about: In the context of such a parrhesiastic Speech Activity, as Foucault called it, the women involved in the project formulate their biographies, which they had previously developed together with Möntmann and her team. The second focus of the project is the creation of diagrams, consisting of the crimes committed by the women (I) in juxtaposition with the crimes committed against them (II). As an artist and scientist with more than twenty years of experience in prison projects, Ulrike Möntmann is curious to see how the invited Accomplices will evaluate the inclusion of artistic elements in research.

Veronika Hofinger from the Institute for the Sociology of Law and Criminology at the University of Innsbruck has been working on the (women's) penal system for quite some time and has also conducted interviews with prisoners, including those in the Schwarzau prison, as part of her studies on violence in custody. Her current project focuses on digitalisation in prisons, the severely restricted access to the outside world via the internet, especially for women. What she finds particularly fascinating about Möntmann's project is the successful encouragement of parrhesiastic Speech Activity: for example, Esma Bronkovič, one of the project participants who will be mentioned frequently in the following, wrote great, impressive raps about her life as part of the project.

Johanna Meier studied psychology and later acting as part of her teacher training. She has experience in addiction support and currently works in youth coaching, an Austria-wide project that offers ‘training advice to young people at risk of exclusion at the end of their compulsory schooling’. It is therefore a matter of large-scale support and mediation work within the framework of a broad cooperation network.

Monika Stempowski has many years of experience in the field of dependency disorders and has been conducting empirical research at the Faculty of Law at the University of Vienna for ten years now, with a focus on the criminal and forensic commitment of mentally ill persons. The graduate psychologist and lawyer also initially worked in addiction support, after which she completed her training at the Schweizer Haus Hadersdorf Wien and cared for pregnant drug-dependent women at the University Hospital of Vienna (AKH).

I. Language barriers

Monika Stempowski is particularly interested in the aspect of language as an instrument and technique of communication, which is also of particular importance for the PARRHESIA project. However, such communication, for example, about the reasons for a judgement, is not only difficult between the judiciary and the accused or convicted person but is also almost impossible between lawyers and psychologists, even if they are talking about the same facts of the case. Because ‘terms are used, maybe they are the same terms but with different meanings; maybe they are different terms that mean the same thing; then there are legal terms that are supposed to describe a psychological phenomenon, where I, as a psychologist, think: “I'm not sure exactly what that means, so in our terms, it doesn't make sense”.’ In addition to the terminology, it is also the internal logic of the various fields that can be difficult to translate. ‘In this respect, I find this linguistic aspect,’ says Stempowski, concerning the PARRHESIA project, ‘illuminated from a completely different angle, namely the artistic side, which is very, very interesting.’

Ulrike Möntmann confirms this diagnosis from her own experience: in the Expert Meetings for the previous project, she found that although there was great mutual interest in the respective professional expertise, the lack of a common language often meant that no real insights could be developed; instead, a kind of ‘tourist’ curiosity prevailed. That is why she introduced the Accomplices‘ Meetings into the accompanying reflection process, ‘to get this knowledge out into the world,’ as she emphasised after mentioning the core concern of the ‘circulation of knowledge’ of her OUTCAST REGISTRATION.

However, the project's difficulties began much earlier, as Stefan Auberg now reports. The documentation of their efforts to get in touch with suitable prisons in Northern and Southern Europe, which already comprises 182 pages, is therefore also a chronicle of failure: there was little willingness, they were often ‘simply slammed in the face,’ which ultimately led them to change their strategy. New contacts were made through independent researchers in the respective countries who deal with the topic of detention in the broadest sense, and these have now given rise to hopes of projects in Finland and the Czech Republic. On the other hand, in Austria, at least in some institutions, there is a relatively high level of willingness, as Veronika Hofinger and Ulrike Möntmann unanimously state. Overall, however, it can be observed that so-called international ‘model institutions’, which are particularly progressive in areas such as women's imprisonment and digitalisation and also communicate this to the outside world, are hardly accessible because they are simply inundated with requests.

II. Educational opportunities

One such model institution is in Norway, for example, which is particularly committed to providing educational opportunities for prisoners, an aspect that also concerns Ulrike Möntmann. In her experience, these are usually ‘terribly depressing’: from shrink-wrapping cheese to sorting lids for motor oil containers to screwing chair legs for a large Swedish furniture store. Not being offered a suitable, sustainable training programme seems to Ulrike Möntmann like an unspoken but particularly effective additional punishment. Johanna Meyer sees a parallel to free society in this because even in prison, only those who are already privileged receive support for apprenticeships that are in demand on the labour market – everyone else can only succeed in these with enormous effort, but usually not at all. Ulrike Möntmann adds that in her experience, it often leads to ‘auxiliary functions’: ‘you then become a kitchen assistant to the kitchen assistant’. According to Monika Stempowski, this is again due to the widespread language problem, for example, between inmates and prison staff; here, it is initially less about a specific terminology than about a fundamentally shared language. On top of that, there are massive staffing problems: court officials have to deal with security issues first and foremost, which are already almost impossible to manage; additional activities, such as supervising inmates in workshops for training purposes, are usually not even possible. ‘This means that the first thing to be eliminated is daytime activities, work in prison.’ And young people, who are often now serving short sentences, have no chance of completing an apprenticeship – ‘a paradoxical result’ of efforts to reduce prison sentences and take other measures instead. But what happens when they are released? How can the necessary ‘transformation’ succeed? Although initial efforts are being made, they are still far from sufficient overall.

From her conversations with the imprisoned women, Stefanie Elias has the impression that the younger ones in particular, who are serving longer prison sentences, are not sufficiently informed about training and employment opportunities. Veronika Hofinger's experience, on the other hand, is that more is invested in supporting adolescents and young adults in prison than in offers for older prisoners. ‘One inmate who was keen to learn [...] told me she had been waiting seven months for a crochet class and then she got it [...], and then she wasn't allowed to take any other classes.’ This, in turn, is probably also related to the Vocational Training Act, which also requires the prison to offer school and vocational training up to a certain age – but only up to that point.

RAP recording ‘MAMA HÖRT MICH VON HIER DRINNEN NICHT’ by Esma Bronkovič

III. Diagrams put to the test

Ulrike Möntmann now presents the second core element of her project: the ‘crime diagrams’ – one by Rebecca Mertens from TBDWBAJ and the other two diagrams created so far as part of the PARRHESIA project. These visualise the crimes (I) that the women involved have committed and for which they have been convicted, in contrast to the crimes (II) that have been committed against them, usually since early childhood, and only rarely punished. What interests Ulrike Möntmann here is the legal view of the proportionality of the crimes (I) and (II), especially since there were inconsistencies, misconduct and omissions on the part of both the ‘human-moral’ and the legal side, including the alleged use of force, which first and foremost had and have fatal consequences for the women. However, such open criticism of the glaring weaknesses in the procedures and practices, not least of the institutions involved, could make future cooperation more difficult, as Stefan Auberg points out. However, to keep quiet about them because they are ‘only’ based on the women's accounts is by no means the solution, says Veronika Hofinger, even though she has already experienced the fact that, alarmingly, little attention is paid to the prisoners' statements. Blanket condemnations of institutions are also not fair or helpful here, she says, adding that the best approach is to be precise when naming the source. Sometimes, however, the anonymous route via external bodies has to be taken, which is then the best and safest way to ensure that a complaint is heard, adds Johanna Meyer.

Monika Stempowski returns to the goal of the project, which needs to be defined: is it to document events that have already occurred or is it about prevention? ‘These are two very different issues with very different impetuses for action,’ which must be clearly stated even when the interests of the cooperating individuals and institutions conflict, and which include both the methodology and the evaluation and awareness of subjective representations. The keyword here is ‘integrity of the work’: ‘There are things that have to be criticised, that have to be named as such, but not [...] with a one-sidedness in one direction or the other – just to say that everything the [prisoners] tell us can be ignored anyway [...] would be a disaster. And, conversely, to say that what the system does [...] is always harmful for those affected [...] is just as bad. It is so important to try to show the various areas of tension as they are, and to do so with precision.’ In Stempowski's opinion, the contexts of the reported experiences should be treated with all the more caution: ’One is the context of perception and experience, and the other is, for example, a legal assessment.’

IV. Terminological questions

The term ‘cruelty’ is a good example, Monika Stempowski continues, which can certainly be used in the legal assessment of an offence and can lead to a higher sentence; in the diagrams presented, however, it was not used in this way. ‘Prose of the acts or the crimes,’ Ulrike Möntmann notes, ‘because we are not lawyers’. Despite handling the collected data with the utmost care, her approach is: ‘I ask about the events [...] and I assume that I am being told the truth. I have no reason to doubt it.’ Stefanie Elias points out once again in this context that the diagrams are still preliminary versions, which raise questions regarding both the technical data processing and the legal interpretation.

As for the question of legal classification, Monika Stempowski admits outright: ‘I don't dare do that’ because, in this specific case, she lacks both historical and substantive expertise. ‘How is this testimony to be assessed? Is this person to be believed? Based on this, the court then subsumes these facts and a specific set of circumstances. But that is very, very time-consuming and very complex legal work, for which a great deal of information must also be available. Much more information than ‘I was beaten’ or ‘I had bruises’.’

Veronika Hofinger, on the other hand, doubts that this is necessary at all in the case of Rebecca Mertens (as well as Esma Bronkovič and many other women) – for the credibility of the mother's failure to provide assistance in countless cases, no paragraphs are needed. And Ulrike Möntmann also insists once again on the unmistakable disproportionality of the prison sentences for Rebecca Mertens and the systematic sexual abuse to which she has been subjected since infancy.

Monika Stempowski finds the idea of the confrontation completely plausible, but continues to wonder whether it is helpful for the presentation of the individual fate on the one hand and the other hand whether it might endanger Ulrike Möntmann's project in that she could make herself vulnerable in terms of the completeness and correctness of the information and ‘that what it is about, namely the experience and the burdens and assaults and aggressions that she has experienced, that this is then actually devalued again’. In the following, further inaccuracies in the legal vocabulary of the diagrams are critically examined, such as the difference between administrative, monetary and custodial sentences, as well as alternative measures (diversions or sanctions). Overall, the critical discussion brings to light an important insight: the legally meticulous balancing of offences against each other in the context of the diagrams is not at all necessary to illustrate the system's failure concerning women.

Another question regarding the visualisation concerns the fundamental inclusion of offences committed by women below the age of criminal responsibility, including, for example, stealing grandma's cigarettes at the age of seven, which may not have had any legal consequences but certainly had violent educational consequences in the family environment. The team around Ulrike Möntmann gratefully accepts the important suggestions for correct terminology and categorisation to make the corresponding events, which are still in a state of blatant imbalance, even more comprehensible clearly and correctly. As in the case of Ivana Landmann, who has one of the ‘worst biographies’ Ulrike Möntmann has ever recorded. Ivana, who is now 38 years old, has already spent 17.7 years in prison – while the perpetrators, her biological father and stepfather, have not been held accountable at all or have only been given a few years in prison. After his early (!) release, the stepfather reported Ivana, who was five years old at the time of the offence, for ‘seduction’.

All of this leads to the question of how multiple offences, convictions and prison sentences are related, which Monika Stempowski summarises as follows regarding the different international legal systems in Austria: ‘In principle, one can say that a person is accused of various offences, which [the court] treats together and passes judgement on in one verdict. And for these offences, the person receives a sentence based on the strictest possible penalty.’ For the diagrams of the PARRHESIA project, whose analysis process is still in its early stages, as Ulrike Möntmann admits, this means a review of the legally correct assignment between criminal record entries and periods of imprisonment. In her view, however, the question of the not only legal consequences of an offence for the person, which can be visually experienced with the help of the diagrams, remains interesting.

V. Biographies

Before the presentation of one of the biographies developed in the context of the project, the thematic diversity of the discussion once again picks up speed. First, the ‘Matrix method’ developed by Ulrike Möntmann for this purpose is discussed, which has already been effectively used in TBDWBAJ. The women can select from a catalogue of pre-printed words those that are suitable for their respective life stories; ‘they are terms,’ explains Möntmann, ‘that I believe could be used to tell almost any life story.’ But, as she explains in response to Veronika Hofinger's question, there are, of course, target group-specific differences, for example with the word ‘love’, which rarely occurs among drug-dependent women, usually only in connection with children.

However, Möntmann is once again concerned about the question of the disproportion between Rebecca Mertens' crimes and her sentences. ‘Imprisonment per se’ does not make sense, says Monika Stempowski, and this is also the consensus in criminology: “Imprisonment in itself, if you don't do anything else, does harm.” At best, positive effects can be achieved through therapy and further training opportunities, as well as through targeted “transition management” into freedom as part of a structured “resocialisation process”. But the crucial point lies much earlier, she continues, namely ‘in the fundamental criminalisation of the people who acquire and consume the substances.’ This much-discussed question of legalisation is handled quite differently in different countries and requires coordinated regulation, for example with the United Nations. But there is agreement on the harmful nature of criminalisation: ‘That alone gets us nowhere.’

The discussion group is now extended to include Barbara Kraml; in her dissertation, the lawyer and political scientist has theoretically examined the relationship between norm and normalisation, following Foucault and Butler, which prompts Ulrike Möntmann to return to the ‘stumbling block of language’ discussed at the beginning. After all, the stated aim of the Accomplices' Meeting is “to be able to understand each other in the sense of an interdisciplinary understanding”. But that would also mean translating legal terminology into everyday language. Monika Stempowski also sees a need here, as the issue of addictive substances marks an ‘overlapping area’ between legal and psychiatric problems. Stefanie Elias has experienced first-hand how difficult it is to understand criminal records as part of the PARRHESIA project. What do the women concerned know about these complicated documents? Although they are entitled to inspect the files, it remains questionable to what extent they actually exercise this right, or rather, whether their defence lawyers encourage them to deal with it in a very concrete way, says Barbara Kraml.

Ulrike Möntmann then talks about a woman who was the first Sinti to take part in one of their projects. As part of Speech Activities, she read the paragraphs that were entered in her criminal record; at first, it was difficult and ‘awkward’, but then she got more and more ‘fluent’. And yet, you can tell from the audio recording how far removed she is from this legal style, the meaning of which she can hardly grasp. Only the repetitive formulations led to a brief ‘aha effect’ at certain points, but above all to amazement that these ‘difficult formulations [...] were about her life’.

Ivana Landmann's biography will be heard and read next. Ulrike Möntmann met with her several times over a period of fifteen years, always with glimmers of hope, such as her starting therapy, but also with the repeated admission that she could not get away from the addictive substances. ‘When I think that she will be released soon or in a few years – I simply lack the imagination [...] where she can go and, above all, how she can actually find a place in society.’ Due to the extreme violence and abuse she experienced, the long periods of imprisonment and the resulting drug addiction, Ivana Landmann is a deeply damaged person, both mentally and physically, without strength, support or orientation. To Möntmann's complete incomprehension, however, she is treated like a completely ‘normal’, healthy prisoner who is supposed to return to a community after serving her sentence. Under other circumstances, a woman of Ivana's constitution would be classified as severely disabled. But when disability is caused by drug addiction, those affected seem to be blamed for their ‘own misfortune’ – which again leads to the question: Who is responsible for all the ‘collateral damage’ of sexual violence in early childhood? More precisely: Who – in very practical terms – takes care of the victims?

VI. Drug use

‘I do get the feeling that, from an early age, this is a form of self-medication due to the massive violence she has experienced and the resulting illnesses that have developed,’ suspects Johanna Meyer. The question is therefore what could have been done for Ivana Landmann in terms of possible alternative medication and also in terms of stabilising training during her detention and further measures. Veronika Hofinger's impression is that the issue of drugs is ignored in many prisons on the one hand, and stigmatised on the other, which Ulrike Möntmann and Stefanie Elias confirm: Although the security staff are usually well informed about the exchange of drugs or medication, for example during outings in the courtyard, and this is always sanctioned, it is often simply tolerated. This is a ‘reality of the prison system,’ notes Monika Stempowski, with ‘the conditions and limits that this system presents. And the limits are enormous for everyone involved. So even the staff don't have the resources and the possibilities or the competencies to react to all these things [...].’ Ulrike Möntmann even encountered a prison director with the following motto: ’[Y]ou always have to make sure that there aren't too many or too few drugs in prison.’ In her experience, prison staff generally have an ambivalent attitude somewhere between a ‘serves them right’ mentality and the realisation that people like Ivana Landmann should be helped with controlled medication, in other words, ‘administering clean, proper heroin for free every day and hoping that [the person] doesn't end up broken in some way’ as a result of the atrocities they have experienced. The problem, says Johanna Meyer, is a lack of concept on the part of everyone involved, which is particularly serious for the released prisoners. ‘I would say she can't get out anymore,’ says Ulrike Möntmann bitterly, especially since neither her parents nor anyone else on the outside will take care of her.

Apart from the behaviour ingrained in prison, the world outside is also a different one after long prison sentences – keyword digitalisation – adds Monika Stempowski. Basically, after release, you have to ‘find something comparable to prison,’ Ulrike Möntmann agrees because Ivana Landmann is at a fatal dead end: she can hardly stand it in prison, but dealing with freedom outside will be at least as difficult. It is, therefore, important to establish a long-term forensic commitment for mentally ill people, as has already begun in some places. This would be evaluated annually and would only release people into the community on condition that there is a safety net. ‘In other words, there is some form of control, there is usually psychiatric supervision, i.e. treatment and monitoring, etc.’ From a ‘purely criminal law perspective, this is very successful [...] because the rates of return are very low. So this form of care, support and control that goes beyond the immediate execution of the sentence is now purely if you aim to ensure that people do not re-offend, very efficient.’ This is one of how the detention order differs from the penal system: ’If someone has served their sentence, then as a rule, that's where my options end.’ All the support services are then purely voluntary. In this context, Ulrike Möntmann tells of an older female offender with decades of drug addiction who was no longer accepted by any therapy facility. She was finally admitted to LÜSA, a long-term transitional and support programme that only exists in Germany. In it, residents who are considered to have exhausted all other forms of therapy may ‘use’ drugs, provided they observe the house rules, and they may also be on substitution therapy, which is not the case in many other institutions.’ Nevertheless, she commented on her admission there with the words: ’Who wants to be a hopeless case?’

VII. A labyrinth full of dead ends

Johanna Meyer now talks about the many support options in Austria, but at the same time admits that a lack of communication and a faltering flow of information between the agencies, institutions and individuals involved are often the problem here as well. Nobody feels responsible for complying with the right to counselling with a real willingness to provide support, especially in the case of addicts and/or young people who often lack cognitive ability (as yet). Stefan Auberg wants to know whether it is easier for men to integrate after their release from prison, with a view to fundamental gender aspects. According to Veronika Hofinger, there is a lack of data on this, but overall the relapse rate is higher on average for men. Furthermore, investments are presumably made in the corresponding ‘cases’ according to the prospects of success rather than need, without regard to gender.

Ivana Landmann is as meek as a lamb, without any genuine criminal energy, says Ulrike Möntmann. She was able to supply herself with drugs for years by stealing a prescription pad. In prison, however, she was suddenly accused of assault, which she did not even perceive as such at first; violence among prisoners, especially in the context of addiction and drug use, is not uncommon in prison. However, this is crucial for the sentence, as it can increase. ‘Drug offences have a highly significant influence [...] on severe physical violence in custody,’ Veronika Hofinger also confirms based on available data.

Ulrike Möntmann now returns to Stefan Auberg's question about gender differences and recounts how the ‘Veelpleger’ law was introduced in the Netherlands years ago, which authorises the state to detain repeat offenders preventively for two years. This programme is aimed exclusively at men, but it was also applied to women, who are far less likely to offend. When asked how this could be, the then-minister of the interior in charge said ‘because women are a negligible phenomenon in prison’ for whom no costly programme of their own should be developed.

Stefanie Elias now addresses the question of whether any figures are showing that imprisonment encourages drug use to Veronika Hofinger, who affirms that there are: Therefore, they try to keep young people out of prison for as long as possible and take other measures like therapy in place of imprisonment. However, the problem here is also a ‘chronic lack of funding’ and ‘staff shortages,’ adds Barbara Kraml, based on her observations in prison Vienna-Josefstadt, ‘which then leads to a setting that encourages physical violence among each other.’ The principle of the Prison Act, which stipulates that young people should be detained separately from adults in the context of ‘the protection of minors [...] in the broadest sense’, does, in principle, already make a distinction between the sexes. However, the group of adolescent girls whose offences are so serious that they are imprisoned is extremely small – which, as Ulrike Möntmann continues, means that this separation is often not taken into account for capacity reasons. Barbara Kraml also confirms this deplorable state of affairs, particularly in pre-trial detention, and even in the large Austrian prisons, adolescent and adult men are separated at best, while girls and women are only rarely separated. Monika Stempowski also draws attention to possible disadvantages in this regard because ‘if you were to strictly enforce this separation from A to Z, the reverse consequence would of course be that the group of people with the least would be unable to participate in a great many things.’ On the whole, it could be said at this point in the discussion the legal regulations for the execution of measures and sentences for mentally ill people are much more differentiated and theoretically open up more possibilities than is the case in reality due to the lack of financial, personnel and spatial resources everywhere.

Another problem is the supply of other medications such as psychotropic drugs and benzodiazepines, which are used in some cases to sedate inmates and in others for self-medication, but often inappropriately. However, this is a general issue in addiction therapy, in which prison psychiatrists play a difficult role.

RAP: ICH HAB MAL WIEDER STREIT MIT MIR SELBST by Esma Bronkovič

VIII. Who carries the consequences?

The final point of the discussion is Ulrike Möntmann's concern to critically examine the existing sex crime law together with the lawyers and psychologists: Why is there no public prosecutor in cases of sexual violence, why is it always left to the victims, who are mostly silent out of fear, shame and guilt? Barbara Kraml believes that this question opens up ‘a whole range of issues [...] with individual areas’. The first problem is that sexual abuse often occurs in childhood in the closest of circles, and few institutions have access to it. Furthermore, the staff in kindergartens, schools, and leisure facilities are not trained enough to recognise such signs and take action. In addition, there are developmental psychological problems of credibility with small children since they usually have a well-developed imagination but no sense of time, which often makes their stories tricky. When the victims can articulate themselves adequately later on, it is often too late to file a complaint due to the statute of limitations, and even lawyers advise against reporting it due to weak evidence – to avoid ‘another slap in the face for the victim’.

Ulrike Möntmann insists that solutions must be found for all of these issues. Veronika Hofinger also finds that the sentences for sexual offenders are often much lighter than those for property crimes. From her own experience as a lay judge, she knows that a robbery with a toy gun or growing large quantities of marijuana, for example, have each led to a higher sentence than sexual offences. The question would, therefore, be whether a higher penalty for sex offenders is a solution, which Barbara Kraml denies. On the contrary, experience has shown that victims would be even less willing to report crimes – especially when it comes to family members – knowing that the perpetrators would then go to prison for multiple years. It is, therefore, more important to raise awareness among all external parties, i.e. ‘to look if there is any suspicion that something could be going on, and what do I have to document then, and how do I deal with it’. Incidentally, this also applies to medical personnel, adds Veronika Hofinger, who should be trained to recognise and document that sexualised violence is involved when examining victims.

In this context, Monika Stempowski once again emphasises the problem of evidence for the court, which is far more complicated in sexual criminal law than in other areas of offence: even with good medical documentation, ‘as a rule, there is nothing [...] for the criminal proceedings, except for the statement of the person concerned. If she does not report it, if she does not testify, nobody can do anything. And even if she does testify, it is different from everywhere else, of course, there is usually no one there, and there is no physical evidence in any form, which means that the only thing the court can do is to question the two people involved. And of course, the principle applies that the court must be so convinced of the guilt that it sentences, and if there is any doubt, it must not sentence [...].’

Ulrike Möntmann returns to her starting point: ‘For me, it's not about [...] more punishment and everything will be fine. No, but it's probably about a great frustration at not reacting to a life-destroying event.’ The violence is simply ‘approved of’. But if you took the victims, the women, seriously and offered them help and support, a lot would be gained. This ‘lack of interest’ is the worst part, Möntmann concludes. Barbara Kraml replies that, to her knowledge, at least in Vienna, there are specialised public prosecutor's offices that deal with crimes in the ‘social environment’, with targeted preservation of evidence and specially trained medical personnel, and that the statute of limitations issue has now been improved by new provisions.

Ulrike Möntmann has often experienced in her projects that women blame themselves for their experiences of sexual violence, whether as a child or later. There are studies that show a link between early childhood sexual violence and later prostitution, says Johanna Meyer, while Monika Stempowski again advises caution on this point, as there is still not enough known about such causal relationships, which is also clear from the biographies of the women presented here, who mostly describe ‘multiple problem situations’ with recurring stresses from early childhood into adulthood. Especially for women who are addicted to drugs, prostitution is often a way of ‘generating funds to finance the addiction’. According to Johanna Meyer, there are at least prevention programmes in which children and young people are instructed ‘to pay attention to their boundaries at an early age so that they can then report such things more easily’ and also learn at an early stage to be able to articulate cross-border experiences. In her opinion, however, the crucial point is the ‘dependence relationships’ that lead to children and young people in particular, preferring to remain silent or cover up and isolate themselves because they fear a complete breakdown of the family, which they then blame themselves for due to their still ‘egocentric world view’, as Barbara Kraml explains. ‘And that's crazy for children [...] an insoluble conflict of loyalty in which you can only support them as best you can. But at the end of the day, you can't resolve it.’ Johanna Meyer says that “the mothers [...] or the other person in each case” also need much more support. In addition to training for kindergarten teachers, teachers, medical staff, etc., she adds that society as a whole needs to pay more attention to each other.

Rebecca Mertens also found herself in a vicious circle of violence and neglect, as Ulrike Möntmann now relates. As a child, she was severely beaten by her mother, who in turn, Rebecca suspects, was also beaten by her grandmother. Years later, the granddaughter is sitting in the same prison where her grandmother was previously imprisoned – making it all the more important to Möntmann that women like Rebecca find places where they are taken seriously. Stefanie Elias adds that such an effect could already be felt on a small scale during the two-week project implementation in the two detention centres: ‘Just the fact that two women come from outside and take the time to listen to the women's stories.’ Many of the women said, ‘I have never told this story before, and somehow nobody was interested.’

IX. What happens next?

For many of the women participating in the PARRHESIA project, it was the first self-chosen work, which they approached with great enthusiasm, says Ulrike Möntmann. They are not just ‘lazy, work-shy people’, as many inside and outside prison believe. ‘Yes, they really want to work, but probably something related to themselves, like all of us.’ Barbara Kraml also sees this labelling as a deep-seated problem: ‘I think [...] that these underlying injuries that have happened to women receive so little attention in the penal system, probably because the focus is only on their isolated behaviour, which is criminally sanctioned, and everything else around it is left out.’ So the fact that they may have been victims themselves and that this may also be a reason why they started taking drugs in the first place is completely ignored. The court is usually not interested in the reasons for the addiction and often does not go very deep, therapeutically speaking, either. Stefanie Elias suspects that the entire apparatus is simply not designed for this. Veronika Hofinger sums up her view on the project with: ‘It simply shows what a small section the judiciary deals with, your project shows that very well.’

Ulrike Möntmann then asks the participants to share their thoughts on the project so far. Veronika Hofinger finds the project exciting and the diagrams are very illustrative. She also highlights the importance of the biographies being told by the women themselves, thus creating an understanding of what happened to the women. She is particularly curious about the presentation of the entire project, which, she says, depends on making it clear that here, a very specific, narrow section is examined, sanctioned, and punished, and thus a certain order is established, but one that has very little to do with what is done to people. This is also important to Möntmann, as she always emphasises in the introductions to the respective project phases: ‘We need each other to make this possible, the project work, this research, so that the issues, the events become a public matter again.’ Instead of hoarding information, the women should ‘have this parrhesiastic courage to stand up and speak out about what happened to them’. That is why she is initiating the exhibition, the project website and the planned accompanying publication – ‘to bring this into the world’. Veronika Hofinger believes that the project highlights the system's glaring deficiencies. The women are simply ‘kept’: ‘And that is a social scandal, apart from the fact that the wrong things are being sanctioned or only a part of them.’

On the one hand, Johanna Meyer is concerned with the question of how the project will continue in the direction of the public. ‘How can this transfer succeed well? Maybe real changes will be suggested? How can it end up with the right people?’ On the other hand, she is interested in the opinions of the women involved, that is, what the project work and the presentation do to them. Were they involved to the extent of expressing their wishes or further ideas about the materials developed? Stefanie Elias and Ulrike Möntmann explain that in the participating institutions, so far the JA Schwarzau and the Schweizer Haus Hadersdorf, there was initially always an internal presentation for the staff and fellow inmates, in which the women could voluntarily participate. In most cases, they did so with equal parts excitement and fear of possible negative reactions, as well as with enthusiasm and pride when they finally received encouragement and confirmation from others who had experienced similar things but had never previously revealed them to each other. At that moment, they felt seen.

Johanna Meyer emphasises once again the point of ‘society's responsibility’, ‘this renewed encounter’. She suspects that the massive experience of violence that comes to the fore in the biographies will seem far removed to most people; at the same time, however, it would become clear that these are ‘completely normal’ people who were just trying to build a life. This consideration is also reflected in the digital maps with the respective locations of the biographers on the project website, which, as Stefan Auberg explains, establishes a geographical, but above all emotional connection. In addition, Ulrike Möntmann is working on a sound space in which the biographies and Speech Activities can be experienced.

Stefan Auberg points out another aspect of reception, namely that of the experience of art, which naturally also plays an important role here, since ‘this is a very difficult topic’; ‘so wanting to deal with it requires a lot of personal initiative and interest. And just as art is often experienced, it is an aesthetic motivation or possibly a slight historical educational mission, but weaving this very specific topic into a publicly accessible exhibition has a lot of pitfalls or a lot of complications to get people there at all.’

Stefanie Elias can already see complaints coming that it is not ‘suitable for children’, which is why her team has already considered trigger warnings, for example, for the project website. Johanna Meyer suggests including ‘links to offers of help’. Ulrike Möntmann, however, is clear: ‘Not likely. That would mean leaving my area of art and science; I absolutely want to remain cautious,’ that is, not to claim to know what to do or to persuade someone to deal with it with a raised index finger.

In response to Veronika Hofinger's question about the percentage of women with drug problems in prison, Ulrike Möntmann replies that experience shows that it is usually a good 60 per cent or more but that they usually fall through the cracks of the statistics because they are usually imprisoned for theft and similar offences and not for drug use. This is important information, says Hofinger, because it means that we are not talking about isolated cases here. It is ‘not a niche problem,’ Stefanie Elias also states, ‘but rather an issue that determines everyday life in prison.’ Unfortunately, as Monika Stempowski notes, the figures are not systematically collected in Austria – unlike in some other countries. She also very much welcomes the PARRHESIA project overall, particularly the biographies that have been developed, which create a very vivid narrative. However, she emphasises once again the need for corrections in the presentation of life events in connection with drug use and criminal consequences in the diagrams, perhaps even along the lines of the sexual assaults that almost all women have in common. This idea is also supported by Barbara Kraml because it ‘simply makes the typical patterns, typical courses, even more visible’. However, this could also harbour the risk that women who do not fit this pattern but are still drug addicts and offenders are all the more demonised, as Stefan Auberg points out. Especially, as Barbara Kraml adds, they don't want to create the impression that this is a supposedly quantitative evaluation when it ‘only’ contains thirty biographies and is therefore not representative or meaningful. Ulrike Möntmann concludes that the focus on different aspects of the collected data always produces new perspectives and interpretations, which never ceases to amaze her – and that it is the task of art to make all this visible in a way that ‘it is absorbed’.

Barbara Kraml once again emphasises the ‘respectful interaction at eye level’ that she had already taken from the predecessor project TBDWBAJ and the associated publication, ‘also in the way the results were presented’ and in the constant communication with the women involved long after the end of the project, who do not suddenly disappear again ‘as it were as objects of investigation, but remain present, and I find that beautiful’. Ulrike Möntmann then emphasises once again the necessary restraint, which she has sometimes found difficult over the years, when ‘I suddenly found myself telling the women's stories,’ which she says is tantamount to an interpretation that she wants to avoid – the women should speak for themselves. The fact that we depend on each other to problematise social situations and positions is not only a fair deal but also a beautiful (the ideal) way of encountering each other, Möntmann concludes.

Transcript: Stefanie Elias

Summary: Gesa Steinbrink

Participants:

- Veronika Hofinger (VH), deputy director of the Institute for Applied Sociology of Law and Criminology, University of Innsbruck, Austria

- Barbara Kraml (BK), lawyer and politologist, Vienna, Austria

- Johanna Meyer (JM), youth coach, clinical and health psychologist, Vienna, Austria

- Ulrike Möntmann (UM), artist and arts-based researcher, project management, Amsterdam and Vienna, Netherlands and Austria

- Monika Stempkowski (MS), lawyer, clinical and health psychologist, mediator, Vienna, Austria

- Stefan Auberg (StA), designer and project manager, Amsterdam, Netherlands

- Stefanie Elias (StE), actress and director, Vienna, Austria