A debate on the effectiveness of the visual arts as vehicles of intervention in social issues in art space W139 in Amsterdam

Gijs Frieling and Marjolein Schaap moderate the panel. In addition to the experts on the podium, there are experts in the audience as well as members of the public. Those present include representatives of various art movements, general healthcare professionals and those working in addiction treatment, and various representatives from the social sciences and politics faculties.

Marjolein Schaap’s introduction is about Emanuel Lévinas’ theory of the “Other”: “According to Lévinas, the Other is always alien to me and is not my alter ego. Nevertheless, the Other can encounter me and move me, take me beyond my own position.”

The private, the self-centred, needs the antithesis of the public, solidarity, and responsibility. Put more strongly: after the failure of the “grand narratives” (Lyotard),[1] the last remaining truth for us is the inviolable dignity of the Other, only the ethical issue.[2]

Various positions, and questions about the development of the perspectives connected with them, are tabled for discussion: How do we behave with regard to criteria, which we do not yet know or do not actually understand? How effective and how legitimate is it to intervene in social issues utilising the means and methods of the visual arts? How can such interventions, such actions be defined, and what consequences do they have for the artist and for an audience that is involved — possibly unexpected and unprepared? Which responsibilities are taken over by whom, upon who are they imposed? Debate continues about the term “the dignity of the Other” and pondered how the separation of private and public matters, which is viewed as a social construct, can be prevented. The assertion that the group of drug addicts is excluded by society per se is rejected by some of the experts in the audience. The argument is advanced that there are a number of aid providers and institutions, which society funds that are provided for them as participants in society.[3]

ARTA and MDHG clients and carers disagree with this: the practice leaves very much to be desired and does not address all aspects of the problem.

Frieling leaves the podium with the microphone in order to include the heckling experts in the audience in the debate.

Along with others, Hans Kassens points out the situation after the law amendment, the consequences of which have not yet sunk into public awareness, and which hasn’t been trialed long enough; at this point in time it is only possible to speculate. He says that the prior legislation in force in the Netherlands had always been as unequivocal as in neighbouring countries and demanded criminal prosecution of drug consumers, which however had not been enforced. The resulting win-win situation, which came about because of this toleration, is also generally known: Because the state had preferred to provide addicts with medical treatment, it had saved itself a great deal of money that would have been spent on a high number of senseless and cost-intensive prison sentences, and since the 1990s, the number of drug-related deaths has sunk drastically.

This confrontational discussion, remarks an ARTA client, corresponds to the spirit of the times. Since the beginning of the twenty-first century, the consumption of drugs has increasingly been equated with drug-related crimes, and declared as damaging for the economy in the Netherlands. Allegedly, especially the earnings from tourism in Amsterdam, Rotterdam, and Den Haag are negatively affected.

He regards these as excuses, and imputes the general public’s alleged demand for “normen en warden” (norms and values), for the suppression of problems instead of offering tedious and expensive solutions, to the rise and influence of the New Right, which have been meekly taken on board by the government. In general, with the reactionary movements in Europe gaining in strength, a tendency towards zero-tolerance is becoming noticeable, and specifically in the Netherlands also an “anti-toleration attitude”.

An expert from the audience adds that not only in Amsterdam, but also in Zurich, Vienna, Berlin, and other European cities, clean-ups of the inner cities are taking place. Norms are welcomed as standardised guidelines to which people are then adjusted, she quotes Foucault.[4] The politicians Carolien Gehrles and Marieke van Doorninck confirm there has been a rethink of drug policy, because it should conform to the rest of Europe. Like, for example, the “ISD-strafmaatregel”[5] for “veelpleger”, repeat offenders. From 2000 to 2002, the draft law was tested, and in 2004 passed as a bill. Thus, a fare dodger who has been caught ten times and registered, can be sentenced to two years in prison with the goal of re-education.

Greet Kuipers, the psychiatrist on the panel, and the representatives of various aid organisations complain that more or less all measures, like ISD, too, are tailored to drug-addicted men, although they are also applied to drug-addicted women. Based on their experience, they emphasise the urgent necessity for formulating and applying gender-specific treatment guidelines for women. In reality, however, this suggestion is not pursued, because according to the ministry these women, altogether only 4 to 5% of all drug addicts, are merely a “negligible minority”. As an important example, representatives from MDHG report that particularly the female junkies on the Nieuwmarkt, the Zeedijk, and De Wallen are now hardly on the street at all and it is difficult to reach them: “Although illegal prostitution is an offense, the women are usually not prosecuted, merely chased away by the police. In this way, they disappear from the public eye. However, the consequences this can have for the women — to be pushed into Tippelzones (streetwalkers’ patches) like deserted harbour areas without any social control or security, are ignored.” After almost three hours of lively exchanges of expert opinions, personal experience, and points of view, the discussion is closed, and continues in private conversations in the exhibition for a long time.

After the discussion, I feel reminded of Peter Sloterdijk’s[6] comments about globalisation. What consequences does an intervention have in the “cleansed” human zoo in the middle of our comfort zone? Humanism, which everybody accepts as given, and views as their property, has to be constantly reconfirmed and worked on, as recent and contemporary history has demonstrated.

Interventions in socially sensitive issues seem to me a possibility to do this. If the tame world of the consuming members of the educated classes creates both stress and boredom, these two keynotes of existence will always produce discrepancies in communication, a mood of chronic ambivalence, alternating between red alert and immobilisation. An immobilisation that makes an artist on the podium decide to give a junkie in his neighbourhood 25 cents occasionally rather than make the effort to conduct such a project.

This expert meeting took place during the exhibition Love is like Oxygen in W139 – an artist-led production and presentation institution in the center of Amsterdam.

The exhibition Love is like Oxygen is part of the project Liefde in de Stad (Love in the City): Within the framework of this project, Paradiso Amsterdam has been inviting artists, academics, writers, and musicians to use creativity to promote love in urban areas. “It does not concern romantic love,” says Lisa Boersen (Paradiso), “but rather love as a counterpart to fear. The kind of love that makes living together in a confined space more positive.” With unorthodox methods Liefde in de Stad explores – on the interface of art and science – human behaviour in urban culture and the way in which it can be (positively) influenced.

Gijs Frieling, former director W139, writes: „The city is wherever everything has become human. Where nature, with the exception of the human body, has been almost entirely exiled. The city brings out the best and worst in man. Love is a force that only has meaning when given by a free heart. In art, freedom sometimes seems to have become the ultimate objective. This self-determination is also a potential portal to further development, within which artists enter into less non-committal ties with people and ideas. Some of the artists in this exhibition seem to have taken that very step.”

Participating artists: Arno Coenen, Erin Dunn, Gil & Moti, Saskia Janssen, George Korsmit, Ulrike Möntmann, Jonas Ohlsson, Joel Tauber.

[1] See: Peter Engelmann (ed.): Jean-François Lyotard, Das postmoderne Wissen. Ein Bericht. Vienna 2009. For Jean-François Lyotard (1924–1998) the failure of modernism’s project corresponds to the failure of the metanarratives of modernism. These narratives discredit themselves because they are incapable of realising the values of modernism — on the contrary: the metanarratives lead to terrorism and annihilation, because their demand for standardised and total truth is based on a claim to power that negates heterogeneity. The metanarratives are all-embracing ideas that construct society as an abstract model. Lyotard views this as a violation of heterogeneity and individuality; the normativity of modernism’s narratives and the concomitant invalidation of the heterogenous leads to the liquidation of the idea of modernism.

[2]From an article about Emmanuel Levinas by Jan Keij: Plaats en voorbij-de-plaats, wonen en tijd bij Emmanuel Levinas (1906–1995). Kunst en Wetenschap, no. 2, 2004. Keij refers to Levinas’ core thesis, according to which the human self only achieves true dignity if it takes on responsibility for other people. This it is called upon to do by a god, who reveals himself in the faces of other people, in the face of the Other, who is unique and whose mortality demands everyone’s care.

[3]In the beginning, mainly local aid organisations had presented their direct measures, for example, the accessible, daily provision of substitution therapy in “methadone buses”, which are decommissioned city buses at public bus stops. In “spuitruimtes” (fixing rooms), drugs can be hygienically and privately consumed. These rooms were first set up in Zurich already in 1986. To this day, Switzerland and the Netherlands do not agree about which of the two countries was the first to develop and establish progressive solutions. New approaches in therapy were discussed and tested, for example, to administer free heroin to a few incurable or terminally ill drug addicts in Amsterdam — a measure that was regarded as commendable all over Europe. In Rotterdam in 1999, the first nursing home for terminally ill, older junkies was opened. What neighbouring countries admired as a humanitarian act, was regarded in the Netherlands as a pragmatic political measure. From the aid organisations working on the ground, institutes evolved that operated on an interdisciplinary basis, which to serve public health were tasked with specifically researching drug consumption, and developing suggestions for solutions. One of the main contributors was the Trimbos Institute, established in 1996, named after its founder, the psychiatrist Kees Trimbos (1920–1988). Quotation: “the dimensions and the type of this mental ill health is one of the greatest challenges of our society in evolution.” Kees Trimbos, inaugural speech 1969. In: Sociale Evolutie en Psychiatrie, online //www.trimbos.nl/over-trimbos/organisatie

[4]Foucault says that “disciplined normalisation” is the designing of an optimal model, and the operation of discipline consists in adjusting the people to this model. See R. Anhorn, F. Bettinger, and J. Stehr (eds.), Foucaults Machtanalytik und Soziale Arbeit. Wiesbaden: Springer, 2008.

[5]“Inrichting voor Stelselmatige Daders” (ISD) is directed at offenders who are repeatedly found guilty of small offences, such as shoplifting goods worth just a few Euros.

[6]See Peter Sloterdijk [1999], Rules for the Human Zoo: A Response to the Letter on Humanism, Environment and Planning D (2009), vol. 27, 12–28, trans. Mary Varney Rorty; P. Sloterdijk [2005], In the World Interior of Capital: Towards a Philosophical Theory of Globalization, trans. Wieland Hoban, Cambridge: Polity Press, 2013.

Transcription and summary: Nina Glockner

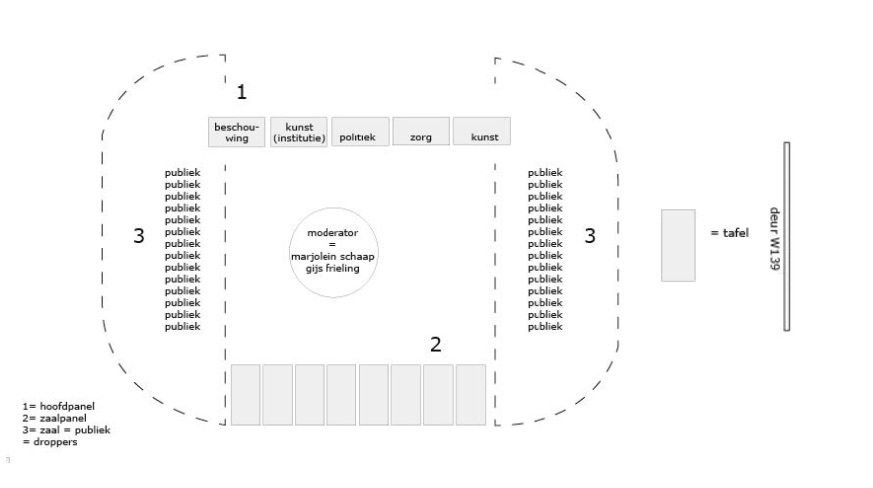

Panel W139. Sketch: Yvonne van Versendaal

A debate on the effectiveness of the visual arts as vehicles of intervention in social issues in art space W139 in Amsterdam

Gijs Frieling and Marjolein Schaap moderate the panel. In addition to the experts on the podium, there are experts in the audience as well as members of the public. Those present include representatives of various art movements, general healthcare professionals and those working in addiction treatment, and various representatives from the social sciences and politics faculties.

Marjolein Schaap’s introduction is about Emanuel Lévinas’ theory of the “Other”: “According to Lévinas, the Other is always alien to me and is not my alter ego. Nevertheless, the Other can encounter me and move me, take me beyond my own position.”

The private, the self-centred, needs the antithesis of the public, solidarity, and responsibility. Put more strongly: after the failure of the “grand narratives” (Lyotard),[1] the last remaining truth for us is the inviolable dignity of the Other, only the ethical issue.[2]

Various positions, and questions about the development of the perspectives connected with them, are tabled for discussion: How do we behave with regard to criteria, which we do not yet know or do not actually understand? How effective and how legitimate is it to intervene in social issues utilising the means and methods of the visual arts? How can such interventions, such actions be defined, and what consequences do they have for the artist and for an audience that is involved — possibly unexpected and unprepared? Which responsibilities are taken over by whom, upon who are they imposed? Debate continues about the term “the dignity of the Other” and pondered how the separation of private and public matters, which is viewed as a social construct, can be prevented. The assertion that the group of drug addicts is excluded by society per se is rejected by some of the experts in the audience. The argument is advanced that there are a number of aid providers and institutions, which society funds that are provided for them as participants in society.[3]

ARTA and MDHG clients and carers disagree with this: the practice leaves very much to be desired and does not address all aspects of the problem.

Frieling leaves the podium with the microphone in order to include the heckling experts in the audience in the debate.

Along with others, Hans Kassens points out the situation after the law amendment, the consequences of which have not yet sunk into public awareness, and which hasn’t been trialed long enough; at this point in time it is only possible to speculate. He says that the prior legislation in force in the Netherlands had always been as unequivocal as in neighbouring countries and demanded criminal prosecution of drug consumers, which however had not been enforced. The resulting win-win situation, which came about because of this toleration, is also generally known: Because the state had preferred to provide addicts with medical treatment, it had saved itself a great deal of money that would have been spent on a high number of senseless and cost-intensive prison sentences, and since the 1990s, the number of drug-related deaths has sunk drastically.

This confrontational discussion, remarks an ARTA client, corresponds to the spirit of the times. Since the beginning of the twenty-first century, the consumption of drugs has increasingly been equated with drug-related crimes, and declared as damaging for the economy in the Netherlands. Allegedly, especially the earnings from tourism in Amsterdam, Rotterdam, and Den Haag are negatively affected.

He regards these as excuses, and imputes the general public’s alleged demand for “normen en warden” (norms and values), for the suppression of problems instead of offering tedious and expensive solutions, to the rise and influence of the New Right, which have been meekly taken on board by the government. In general, with the reactionary movements in Europe gaining in strength, a tendency towards zero-tolerance is becoming noticeable, and specifically in the Netherlands also an “anti-toleration attitude”.

An expert from the audience adds that not only in Amsterdam, but also in Zurich, Vienna, Berlin, and other European cities, clean-ups of the inner cities are taking place. Norms are welcomed as standardised guidelines to which people are then adjusted, she quotes Foucault.[4] The politicians Carolien Gehrles and Marieke van Doorninck confirm there has been a rethink of drug policy, because it should conform to the rest of Europe. Like, for example, the “ISD-strafmaatregel”[5] for “veelpleger”, repeat offenders. From 2000 to 2002, the draft law was tested, and in 2004 passed as a bill. Thus, a fare dodger who has been caught ten times and registered, can be sentenced to two years in prison with the goal of re-education.

Greet Kuipers, the psychiatrist on the panel, and the representatives of various aid organisations complain that more or less all measures, like ISD, too, are tailored to drug-addicted men, although they are also applied to drug-addicted women. Based on their experience, they emphasise the urgent necessity for formulating and applying gender-specific treatment guidelines for women. In reality, however, this suggestion is not pursued, because according to the ministry these women, altogether only 4 to 5% of all drug addicts, are merely a “negligible minority”. As an important example, representatives from MDHG report that particularly the female junkies on the Nieuwmarkt, the Zeedijk, and De Wallen are now hardly on the street at all and it is difficult to reach them: “Although illegal prostitution is an offense, the women are usually not prosecuted, merely chased away by the police. In this way, they disappear from the public eye. However, the consequences this can have for the women — to be pushed into Tippelzones (streetwalkers’ patches) like deserted harbour areas without any social control or security, are ignored.” After almost three hours of lively exchanges of expert opinions, personal experience, and points of view, the discussion is closed, and continues in private conversations in the exhibition for a long time.

After the discussion, I feel reminded of Peter Sloterdijk’s[6] comments about globalisation. What consequences does an intervention have in the “cleansed” human zoo in the middle of our comfort zone? Humanism, which everybody accepts as given, and views as their property, has to be constantly reconfirmed and worked on, as recent and contemporary history has demonstrated.

Interventions in socially sensitive issues seem to me a possibility to do this. If the tame world of the consuming members of the educated classes creates both stress and boredom, these two keynotes of existence will always produce discrepancies in communication, a mood of chronic ambivalence, alternating between red alert and immobilisation. An immobilisation that makes an artist on the podium decide to give a junkie in his neighbourhood 25 cents occasionally rather than make the effort to conduct such a project.

Transcription and summary: Nina Glockner

Expert Meeting, W139, Amsterdam

This expert meeting took place during the exhibition Love is like Oxygen in W139 – an artist-led production and presentation institution in the center of Amsterdam.

The exhibition Love is like Oxygen is part of the project Liefde in de Stad (Love in the City): Within the framework of this project, Paradiso Amsterdam has been inviting artists, academics, writers, and musicians to use creativity to promote love in urban areas. “It does not concern romantic love,” says Lisa Boersen (Paradiso), “but rather love as a counterpart to fear. The kind of love that makes living together in a confined space more positive.” With unorthodox methods Liefde in de Stad explores – on the interface of art and science – human behaviour in urban culture and the way in which it can be (positively) influenced.

Gijs Frieling, former director W139, writes: „The city is wherever everything has become human. Where nature, with the exception of the human body, has been almost entirely exiled. The city brings out the best and worst in man. Love is a force that only has meaning when given by a free heart. In art, freedom sometimes seems to have become the ultimate objective. This self-determination is also a potential portal to further development, within which artists enter into less non-committal ties with people and ideas. Some of the artists in this exhibition seem to have taken that very step.”

Participating artists: Arno Coenen, Erin Dunn, Gil & Moti, Saskia Janssen, George Korsmit, Ulrike Möntmann, Jonas Ohlsson, Joel Tauber.

[1] See: Peter Engelmann (ed.): Jean-François Lyotard, Das postmoderne Wissen. Ein Bericht. Vienna 2009. For Jean-François Lyotard (1924–1998) the failure of modernism’s project corresponds to the failure of the metanarratives of modernism. These narratives discredit themselves because they are incapable of realising the values of modernism — on the contrary: the metanarratives lead to terrorism and annihilation, because their demand for standardised and total truth is based on a claim to power that negates heterogeneity. The metanarratives are all-embracing ideas that construct society as an abstract model. Lyotard views this as a violation of heterogeneity and individuality; the normativity of modernism’s narratives and the concomitant invalidation of the heterogenous leads to the liquidation of the idea of modernism.

[2]From an article about Emmanuel Levinas by Jan Keij: Plaats en voorbij-de-plaats, wonen en tijd bij Emmanuel Levinas (1906–1995). Kunst en Wetenschap, no. 2, 2004. Keij refers to Levinas’ core thesis, according to which the human self only achieves true dignity if it takes on responsibility for other people. This it is called upon to do by a god, who reveals himself in the faces of other people, in the face of the Other, who is unique and whose mortality demands everyone’s care.

[3]In the beginning, mainly local aid organisations had presented their direct measures, for example, the accessible, daily provision of substitution therapy in “methadone buses”, which are decommissioned city buses at public bus stops. In “spuitruimtes” (fixing rooms), drugs can be hygienically and privately consumed. These rooms were first set up in Zurich already in 1986. To this day, Switzerland and the Netherlands do not agree about which of the two countries was the first to develop and establish progressive solutions. New approaches in therapy were discussed and tested, for example, to administer free heroin to a few incurable or terminally ill drug addicts in Amsterdam — a measure that was regarded as commendable all over Europe. In Rotterdam in 1999, the first nursing home for terminally ill, older junkies was opened. What neighbouring countries admired as a humanitarian act, was regarded in the Netherlands as a pragmatic political measure.

From the aid organisations working on the ground, institutes evolved that operated on an interdisciplinary basis, which to serve public health were tasked with specifically researching drug consumption, and developing suggestions for solutions. One of the main contributors was the Trimbos Institute, established in 1996, named after its founder, the psychiatrist Kees Trimbos (1920–1988). Quotation: “the dimensions and the type of this mental ill health is one of the greatest challenges of our society in evolution.” Kees Trimbos, inaugural speech 1969. In: Sociale Evolutie en Psychiatrie, online //www.trimbos.nl/over-trimbos/organisatie

[4]Foucault says that “disciplined normalisation” is the designing of an optimal model, and the operation of discipline consists in adjusting the people to this model. See R. Anhorn, F. Bettinger, and J. Stehr (eds.), Foucaults Machtanalytik und Soziale Arbeit. Wiesbaden: Springer, 2008.

[5]“Inrichting voor Stelselmatige Daders” (ISD) is directed at offenders who are repeatedly found guilty of small offences, such as shoplifting goods worth just a few Euros.

[6]See Peter Sloterdijk [1999], Rules for the Human Zoo: A Response to the Letter on Humanism, Environment and Planning D (2009), vol. 27, 12–28, trans. Mary Varney Rorty; P. Sloterdijk [2005], In the World Interior of Capital: Towards a Philosophical Theory of Globalization, trans. Wieland Hoban, Cambridge: Polity Press, 2013.

Participants:

TEILNEHMER:INNEN

Carolien Gehrles, Politikerin, Gesetzgebendes Institut für Kultur, Amsterdam, Niederlande

Jonas Staal, Bildender Künstler, Rotterdam, Niederlande

Ruud Kaulingfreks, Philosoph, Amsterdam, Niederlande

Greet Kuipers, Psychiaterin, Amsterdam, Niederlande