JUGEND WOHN ZIMMER

Some lives are grievable, and others are not; the differential allocation of grievability that decides what kind of subject is and must be grieved, and which kind of subject must not, operates to produce and maintain certain exclusionary conceptions of who is normatively human: what counts as a livable life and a grievable death? [Judith Butler: Precarious Life. The Politics of Mourning and Violence, 2004]

That delinquents appear to lead livable lives in present-day (Western) prisons in that they are supplied with food and a bed is construed by public opinion as a weakening of the effect of the sanction: the constitutional response to crime must appear to be a credible retaliatory measure.[Michel Foucault: Surveiller et punir. Naissance de la prison, 1975]

Since the gradual disappearance of corporal punishment, public penance, chastisement and torture, starting in the first half of the 19th century, there has been a constant struggle to address the painful question of how to punish without tangible and visible physical force, right down to present-day debates on the modern administration of justice.

The answer to this question was formulated theoretically and very simply back in the 18th century [G. De Mably: De la législation, uvres complètes, 1789] less gruesome actions, less suffering, greater charity, respect, greater humanity lead to an adjustment in the objective of sanctions. That is to say, if the body may no longer be punished, then punishment must be meted out to the soul instead. If the administration of intolerable pain must not impinge on the body, an adequate replacement must be found that makes itself felt in the very depths of the heart, the mind, in a person's will and talents.

JUGEND WOHN ZIMMER (Youth Living Room)

The project takes place in the juvenile wing of the women's prison in Vechta, Germany. The artwork is made up of two parts, action on the one hand and installation on the other, which take shape alongside one another. The action consists of reading stories out loud and setting up a library. The installation consists of a transformation of existing elements of the living space combined with furniture designs that are tailored to the action, which together will make up an installation for reading or living. The objects for the installation are produced in collaboration with detainees in the prison workshops. The work also serves two different objectives: the literature confronts the inmates with their own biographies, experiences and desires, while at the same time, their surroundings are changing. This project can be compared to the slow build-up of tension in a narrative and the reader's gradual identification with the protagonist and action. Parallel to this, the image of the person's own (self-made) surroundings takes shape.

The image is speculative. In applying it, I look for forms, materials and techniques that can help to realize the design. The final image will be based on my proposal (my role being comparable to that of a director) combined with the vision of the participants, which is impossible to predict. The concept itself is based on my personal project experience with detainees.

Prison for girls and young women

The juvenile section of this prison houses about twelve girls and young women aged 14 to 20, from four provinces of northern Germany.

Juvenile wing of the Justizvollzugsanstalt für Frauen, Vechta, Germany. Cells for one or two female detainees. 2005

The section is situated in the old wing of the prison (which was once a monastery) and occupies the entire second floor. A glass partition divides in two the immense corridor or hall (seven metres wide, five metres high and thirty metres long) to reduce conflict. One side ends in large windows, overlooking the small exercise yard, a few trees, the prison wall, and a limited section of the street beyond the wall. The other section of the hall has no natural light source, and is illuminated artificially by strip lighting.

There are six cells on each side, four for inmates and two for the prison guards to use as offices. In addition, each side has an area for communal activities such as watching TV, a semi-public telephone booth and a communal kitchen.

Each cell measures about 4 x 2.5 metres and houses one or two young women, depending on the total number of detainees. The inmates create their own teenage rooms by hanging photos on the walls (within the restrictions imposed by the rules; in principle, the wall space must be easy to inspect, which means that it must either be blank or easy to clear), a wooden bed (especially for juveniles; the other inmates have steel beds), and if there is enough space, a bedside table in between the beds. Each inmate is allowed one cuddly toy. For the rest, the cell contains a washbasin and a toilet, both of which are always within the guards' view.

The hall serves as the inmates living space. It is currently fitted out with a sofa and armchairs in faux „Altdeutsch“ style on a beige marmoleum floor that is kept scrupulously clean. The detainees tend to sprawl here like sacks of potatoes in the shabby living room setting with oak side tables on which they rest their feet, clad in giant Buffalo shoes with huge platform soles. It is a place for talking and laughter. On the surface, you might take gatherings of this kind for social events, but the inmates are not relaxed and the atmosphere is anything but friendly. The inmates do not talk to each other, they shout at each other; they don't ask questions, they presume and mock, curse and issue orders, insult and intimidate: the harshness and stress of life in prison constitute a self-fulfilling, vicious circle of worthlessness, an existence made up of failure and disappointment.

Deal

Enthusiasm regarding any activity in prison, however useful or useless it may be, is generally non-existent in prison. It does not matter whether the inmates are set to work doing mindless tasks in the Plastics section, for instance (such as putting rubber tips onto table legs) or if they are receiving well-intentioned instruction on modelling and glazing ashtrays as part of a pottery course. It does matter, however, that not one of the compulsory or optional activities on offer has anything to do with the inmates' own experiences or their needs. This applies to all detainees, and most especially to the difficult girls and young women in the juvenile wing. This makes it appear during the period of detention that the existing or anticipated drug addiction is the only specific activity in which the intimacy of a familiar pattern and hence the confirmation of a shared experience can be guaranteed.

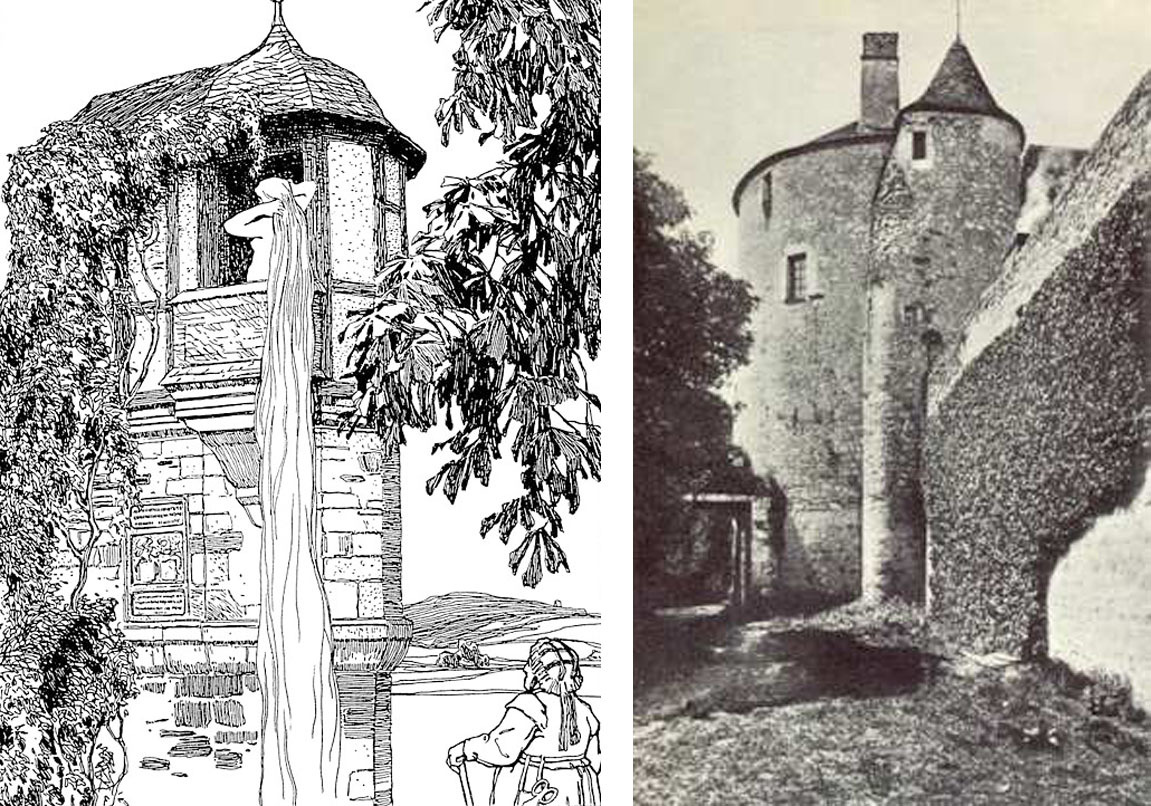

LEFT: Woodcut of Ludwigsburg Tower, in the Black Forest, Germany. The Brothers Grimm identified this as the original tower of the fairy tale Rapunzel because of the specific plants growing in the area. Rapunzel (Radix pontica) ) is a small plant with a thick edible root that is equated with the apple in the Garden of Eden. According to fairy-tale interpreters, living in a turret symbolizes the discovery of thought. The distinctive feature of this fairy tale is that it accords an active role to women, while men take on the passive role of victims.

RIGHT: The Tower, Michel de Montaigne (1533-1592). Montaigne teaches us to see human beings as changeable creatures who are incapable of ever discovering truth. As slaves of their habits and prejudices, egocentricity and fanaticism, they are victims of circumstances. Montaigne includes himself in this harsh judgment; indeed he applies it primarily to himself. Above his own reflections on life, he writes: „I do not teach, I tell.“ Montaigne lived in isolation in his castle tower for years, writing his Essays. His idea of vivre à propos (living life as it should be lived) was reflected in the late 20th-century Real Life school of art [see also Wilhelm Schmid: Ethik der Selbsterfindung. Über produktive Widersprüche bei Montaigne. Kunstforum International, 1999, no. 143]

The execution of each of my prison projects is based on a deal with the detainees. This highly suspicious group of people will run a mile from any educational or therapeutic plans devised in the name of optimistic help and support and from any attempt to gloss over or brighten up their miserable lives. In my approach, I show the detainees my work as an artist and ask them to become part of my artwork, my outcast registration. The invitation to cooperate is totally straightforward: for every new project, I am dependent on their cooperation, and their own views of their lives. I suspect that junkies living in detention see the uselessness of art as rather comparable to the unproductive aspect of drug use, with the option of getting a kick that will temporarily allow them to step outside the oppressive predictability of their situation.

Snow White, Psycho Begbie and Diane

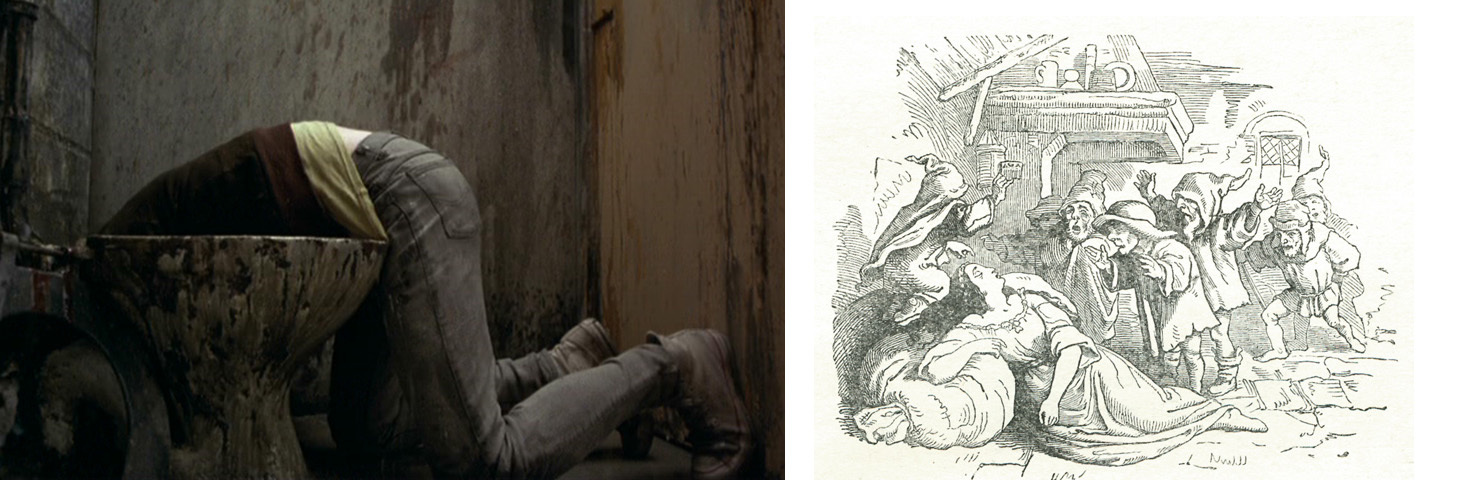

LEFT: Still from the film Trainspotting by Danny Boyle, 1996, based on the novel by Irvine Welsh.

The book and film tell the story of a young vandal, a drug addict who tries to kick the habit and get away from his bad friends. The film features sex, violence, drugs and coarse language, but none of this is glorified. ?Train-spotting?, though originally referring to the hobby of noting train numbers, has come to mean any dreary activity undertaken to help to pass time.

RIGHT: Woodcut by Ludwig Richter, Snow White, Snow White / Unlucky Child.

The narrative begins in the manner of a winter fairy tale. Life is divided into stages of birth, trial, death and revival after death. The mirror on the wall, which is capable of revealing who is the fairest in the land, derives from the magic mirror known since antiquity as a means of predicting how life will unfold. The number seven (i.e. the seven dwarfs) is in part an allusion to the seven cardinal virtues and the seven deadly sins.

The redesigning of the corridor is geared towards giving inmates greater freedom of movement and more physical comfort. The inmates? lives, up to and including their stay in prison, have been an accumulation of events in which their demands for attention have been ignored. From their perspective, attention is a phantom vision of being unharmed in middle-class surroundings, of what life would look like if you did not have to live in this situation, and most especially the desire that everything will turn out well in the end; faithful to the fairy-tale genre and unrealistic. But cherishing a legend is something that none of them has ever experienced; none of them knows the intimacy of being read to, which can help to affirm one's experience of the world

The literary action is the part of the project relating to the imagination. From the very beginning of the project, one of my main focal points is telling stories, listening, and endless repetition. I am convinced that I can reach the girls with fairy tales, from Snow White to the heroin-injecting Psycho Begbie and the 14-year-old Diane in Trainspotting, that is to say, ranging from a princess's dream to a nightmare. My other focus is on creating the installation in the interior of the two-part hall; my ideas about the interior are a continuation of the narrative in a three-dimensional context.

All the designs are made in the prison's own professionally equipped workshops (wood, metals, textiles). Various types of craftsmanship are used in the making of each object, sometimes applied in a spectacular way, such as the construction of a knitting spool with a diameter of 1.20 metres and the knitting of 2-cm-wide prison blanket strips as covers for the sofas. Upholstering with imitation leather, making felt bean-bag seats and sewing futons are techniques that are easy to learn.

The two hall spaces both function autonomously: the glass partition makes it possible to combine the two areas visually. The spaces will be furnished with flexible standard items of furniture, such as tables and chairs for working, comfortable chairs for lounging in, reading and telling stories, and a library on each side which will be expanded on a regular basis. The only fixed object will be the bookcase; all other objects will be mounted on heavy wheels to make them movable.

The design of the two spaces will be harmonised; the use of colour and shapes in the front section, with its large windows, will be restrained. The area for hanging out consists of long, rectangular sofas (three elements, each measuring one metre in width and two metres in length) that can be combined in different ways. Their upholstery is based on the futon technique, which involves combining and stitching pieces of cotton fabric. For the armrests, we are sewing heavy, moveable boomerang-shaped cushions. All the seats are to be covered with the (much-loathed) grey prison blankets. As a whole, the result is suitable for the construction of anything from a hut to a smart design lounge suite.

Sofa, 400cm x 100cm. Wood, futon, prison blankets. 1998 Boomerang cushions, 100cm x 50cm. Prison blankets, heavy stuffing. 1998 Cover, 600cm x 100cm. Prison blankets, made with spool knitting, Ø100cm. 2000 All objects by U.M. The images serve as examples of the chosen form and style of the installation on the front side of the living hall.

In the rear section of the hall, a number of architectural changes will be made before the interior is furnished, the aim being to create a source of daylight, however small. For the rest, this gloomy area will be turned into an extraordinary space somewhere between a UFO and a princess's room. The basic colours will be pink, yellow, and light blue (in some parts maybe metallic); the basic materials will be real and imitation leather and fine wool, woven or felted. The hanging-around space will consist of eight pouffes on wheels, resembling beanbag chairs, which combine to make a wide circle (4 meters in diameter) but which will also provide comfort and warmth in other arrangements, and each one of which can be used as a riding throne. The walls will be covered with luminous imitation leather panels.

Installation, leather sofas, strip lighting, elements made of synthetic materials, 1996, Bastienne Kramer.

The image serves as an example of the choice of form and style in the rear section of the hall.

The existing furnishings of the living area (in dated „Altdeutsch“ style) on both sides of the hall will be dismantled and reassembled into a new piece of furniture that will be the ideal object on which to laze about. The wooden elements will have texts that are meaningful to the inmates carved into them.

IMAGES ABOVE: Living hall in the juvenile section of the prison

The chairs and the tables for one or two people are functional in terms of design, material and colour. The tables can be pushed together to make one large surface or set up as separate workplaces, either for individual activities or for workshops, for instance in relation to a piece of literature or a film.

Besides the basic interiors I am designing for the living spaces, I want to change the TV area into a mini cinema in which films are shown. The section's new internal archives will also be built up here. The computer areas will be integrated into the hall's new interior; my aim is to mobilize the equipment so that it also serves a function within the living space.

Butterfly chair, 125cm x 90cm x 80cm. Design from 1938, upholstered with prison blanket, 1998

The concept for JUGEND WOHN ZIMMER was developed in response to a request by the prison governors, after the Prison Clothes Collection project in 2001. The concept and the plans for its implementation met with an enthusiastic response from staff of the juvenile section, the governors, the Ministry of Justice in Lower Saxony, the Judicial Council for Prison Employment and the Monastic Council. For purchases of books and DVDs, retail stores with interest in the project in Lower Saxony pledged their advice and sponsorship.